It’s been one of the worst winters on record in the eastern United States: epic snowfalls in Boston, thunder snow in New York, fire and ice in Philly. With a temperature of 3 degrees in the City of Brotherly Love and a wind chill of 16 below, firefighters had a challenging job containing a blaze in a three-story medical building on Locust Street. By the time the fire was contained, icicles hung from the end of the fire hoses and the building the firefighters saved was covered in ice.

It was a sight that would have been familiar to Doc Holliday, as he spent two icy winters in Philadelphia in 1870-1872 while he attended the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery. In those days of open fireplaces and coal stoves, house fires were a constant threat, especially in the cold months when the heat was most needed. But Philadelphia was fortunate in having the country’s first Fire Department, founded in 1736 as a volunteer service with assistance from Benjamin Franklin. In the late 1860’s, city officials started plans to transform the volunteer service to a professional fire department, and in 1870, the year John Henry Holliday arrived at dental school, an ordinance was passed to create the Philadelphia Fire Department.

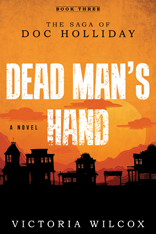

The Philadelphia Gazette was filled with stories of the newly-made fire department and the iced-over buildings when their water hoses were turned on house fires. But the biggest challenge the department faced was frozen fire hydrants, when no water flowed at all. Those were the kind of real-life stories that inspired some of the events in Southern Son, the first book of The Saga of Doc Holliday. The following excerpts come from the chapters set in Philadelphia, bringing John Henry Holliday’s dental school years to life. Enjoy!

From Chapter Eight

It was hard to get back to work again when January came and the winter session of school began. He had gotten so used to staying up past midnight and sleeping until noon that the eight o’clock clinic hour seemed more like the middle of the night. And the weather didn’t help any, snowing heavily and dropping to a low of five degrees, then warming up just enough to melt the snow and leave a slippery sheeting of ice on the cobblestone streets and brick sidewalks. The river froze solid above the Schuylkill Dam, and steamships in the Delaware had to maneuver around the ice. The newspapers were filled with stories of ice injuries: sprained ankles and strained backs, broken limbs and head concussions, and the tragedy of a boy on Race Street who fell to his death while leaning out a third-story window trying to catch an icicle. Yet the locals said it was a mild winter, all things considered, and John Henry wondered what bad weather was like in Philadelphia.

From Chapter Nine

The year before had been mild as far as Yankees were concerned, though John Henry had thought the temperatures less than temperate. But that winter of 1871 was too cold even for the hardy people of Philadelphia who complained that it was the worst season they had ever seen. For a boy from South Georgia, used to lazy humid summers and pleasant sunny winters, the cold was nearly deadly.

It started with a heavy rain that November, causing a three-foot rise in the level of the Schuylkill River where the waters turned turbid and the channel was choked with tree limbs and debris. All across the city, fences collapsed and awnings came down, taking out the telegraph lines and leaving Philadelphia deaf and mute for a week.

By Thanksgiving Day, when the Yankee General George Meade made a show of reviewing the troops at Fairmount Park, the rain had turned to sleet, freezing the shallow ponds around the city and filling the street gutters with ice. But the glistening streets didn’t stop the throngs of promenaders from taking their traditional stroll in front of Independence Hall, nor did it dampen the spirits of the laughing children who played in the congealed standing water at the excavation site of the new City Hall. It was early winter, that was all – and only the frozen fire hydrants seemed any real cause for concern.

But when Thanksgiving passed and December began, the weather turned more bitter still. With the temperature hovering just above twenty degrees, the gutters froze over and water pipes burst, flooding the cobblestone streets with ice and mud. The Schuylkill River froze over, too, the ice forming so rapidly that boats were bound fast in it. Even the Delaware was closed above the city, the channel between Philadelphia and New Jersey filled with floating ice.

For the first time since John Henry had arrived in Philadelphia, the streets were nearly deserted of traffic as everyone not needing to venture out stayed indoors enjoying the warmth of Franklin stoves and tight-shuttered windows. But the stuffiness of the overheated rooms made John Henry even more uncomfortable than the cold did. He wasn’t used to so much dry heat, as the hot air parched his lungs and left him with an irritating sore throat. And by the end of the fall session and the last clinic day before Christmas, he was anxiously looking forward to spending an evening walking from one tavern to the next breathing in the stiff cold air and sipping whiskey until his sore throat was numb.

But one night of whiskey didn’t help much and the next morning he woke feeling achy all over, the irritating sore throat turning into a raspy cough. And though he needed to get started on his vacation work of researching, writing, and polishing his doctoral thesis, he couldn’t seem to find the energy to do it. He opened his books and tried to focus on the pages of dental pathology and therapeutics, but his head felt so heavy that he could hardly keep reading. And he was sweltering, even with the window shutters thrown wide open. If only he could get cooled down, wave away the heat that was rising up inside of him, he might be able to get to work…

Outside, the thermometer on the wall of the Merchant’s Exchange registered a noon high of ten degrees while Chestnut Hill reported a temperature below zero. It was the coldest December day on record and John Henry slept with his head on his books and the freezing air filling his open-windowed room. But with the fever that raged inside of him, he didn’t feel the chill at all.

Fun Links

Fireman’s Hall Museum of Philadelphia

Union Fire Company

Benjamin Franklin, Fireman

Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery

Click the book cover below for more info or to order.