Doc Holliday, Margaret Mitchell and Me

This is the story of a house, and a family, and a legacy, and a legend. It’s also the story of Margaret Mitchell and Gone With the Wind, of Wyatt Earp and the OK Corral. But mostly it’s the story of a boy named John Henry Holliday. And it all started with a house.

This house, the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House in Fayetteville, Georgia. It’s been standing here since the 1850s, watching the world go by: small town folks walking to Church, Yankee soldiers marching toward battle, model T automobiles bumping along dirt roads before the asphalt pavement came, sweltering summers and snowy winters, prized green roses planted one spring and blooming for a generation and sapling trees that grew taller than the roof. It’s been the home of three families and welcomed dozens of cousins and kin; housed the first telephone answering service in town; stood vacant and lonely until it became a museum and welcomed company again. It’s full of stories, this house. I guess that’s why it spoke to me. I like old stories and old houses.

This is me. My name is Victoria Wilcox, and I knew from the first time I saw the Holliday House that I was part of its story somehow. “Mommy’s going to do something with that house, someday,” I’d tell my little girls when we’d drive by. Maybe I’d open a restaurant, something with an Old South theme: “Belle Watling’s Place” perhaps, playing on the Gone With the Wind look of it. Not that I like to cook all that much or ever wanted to own a restaurant. I’m actually just a writer with a big imagination and a love of all things historical. And I wasn’t even sure the house was authentically old. It could have been one of those 1950’s colonial reproductions you used to see on TV. Being a busy young mother in those days, I never had the time to stop and ask. But the house still whispered to me, every time I drove past.

This is me. My name is Victoria Wilcox, and I knew from the first time I saw the Holliday House that I was part of its story somehow. “Mommy’s going to do something with that house, someday,” I’d tell my little girls when we’d drive by. Maybe I’d open a restaurant, something with an Old South theme: “Belle Watling’s Place” perhaps, playing on the Gone With the Wind look of it. Not that I like to cook all that much or ever wanted to own a restaurant. I’m actually just a writer with a big imagination and a love of all things historical. And I wasn’t even sure the house was authentically old. It could have been one of those 1950’s colonial reproductions you used to see on TV. Being a busy young mother in those days, I never had the time to stop and ask. But the house still whispered to me, every time I drove past.

Then my parents came from California on a visit. They wanted to see some local Georgia history, so I made a phone call to ask about the old white house and found out something amazing: it was not only old, but the home of the uncle of Doc Holliday. “You mean THE Doc Holliday?” I asked the nice man at the Historical Society, “from the OK Corral?” As a native Californian, I knew my Western history: Doc Holliday was a Georgia-born dentist who went west to Tombstone, Arizona and fought alongside lawman Wyatt Earp. But if I ever gave him a thought beyond that, it wasn’t set against the backdrop of a white-columned house in a sleepy Southern town. Yet there he was, a sandy-haired boy coming to visit his uncle in the last days before the Civil War and sleeping over at the Holliday House – the house built in the 1850’s, the same era that he was born. Doc Holliday and the house had something in common, and both of them wanted me to know about it.

Then my parents came from California on a visit. They wanted to see some local Georgia history, so I made a phone call to ask about the old white house and found out something amazing: it was not only old, but the home of the uncle of Doc Holliday. “You mean THE Doc Holliday?” I asked the nice man at the Historical Society, “from the OK Corral?” As a native Californian, I knew my Western history: Doc Holliday was a Georgia-born dentist who went west to Tombstone, Arizona and fought alongside lawman Wyatt Earp. But if I ever gave him a thought beyond that, it wasn’t set against the backdrop of a white-columned house in a sleepy Southern town. Yet there he was, a sandy-haired boy coming to visit his uncle in the last days before the Civil War and sleeping over at the Holliday House – the house built in the 1850’s, the same era that he was born. Doc Holliday and the house had something in common, and both of them wanted me to know about it.

Photo Credit: OK Corral Ad – The Town of Tombstone. Circle KB Cowboy Holsters & Western Mercantile

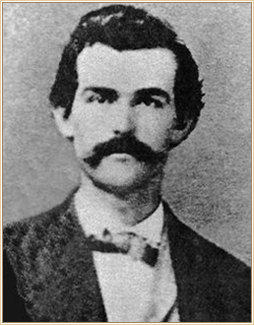

This is Doc Holliday. Handsome, huh? Long story short, the Holliday’s house had me at hello. It was soon to be vacant, and I was soon to form a community action group and then a non-profit organization to purchase the house and restore it to its antebellum beauty. And that’s how I became founding director of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House Museum. We opened to the public in July of 1996, on the day the Olympic torch came through town on its long run toward Atlanta, which was the same day that the new fountain was dedicated in downtown Fayetteville. My little red-haired boy Ross was given the honor of turning on the fountain for the first time. The city fathers said he represented the future of Fayetteville, while his mother and the Holliday House represented the past.

This is Doc Holliday. Handsome, huh? Long story short, the Holliday’s house had me at hello. It was soon to be vacant, and I was soon to form a community action group and then a non-profit organization to purchase the house and restore it to its antebellum beauty. And that’s how I became founding director of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House Museum. We opened to the public in July of 1996, on the day the Olympic torch came through town on its long run toward Atlanta, which was the same day that the new fountain was dedicated in downtown Fayetteville. My little red-haired boy Ross was given the honor of turning on the fountain for the first time. The city fathers said he represented the future of Fayetteville, while his mother and the Holliday House represented the past.

This is Ross at the Fayetteville fountain on the day of the Olympic Torch celebration. He was four years old that summer, and thought all Mommies wore hoop skirts and ran museums……

This is Ross at the Fayetteville fountain on the day of the Olympic Torch celebration. He was four years old that summer, and thought all Mommies wore hoop skirts and ran museums……

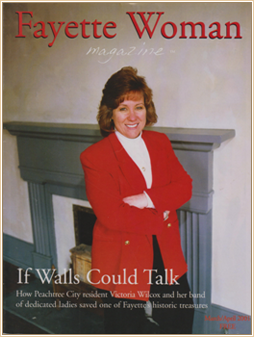

…and had their picture on the cover of magazines. This is from a story about the work of the Holliday House Association. We were honored!

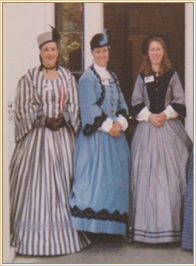

And this is me with the lovely ladies of the Holliday House, dressed in authentic antebellum costumes (I’m the one in blue with the black feathered hat). The best thing about hoop skirts is the way they let the breeze blow past your legs. Summers are mighty hot in Georgia.

And this is me with the lovely ladies of the Holliday House, dressed in authentic antebellum costumes (I’m the one in blue with the black feathered hat). The best thing about hoop skirts is the way they let the breeze blow past your legs. Summers are mighty hot in Georgia.

And winters are mighty chilly! This is Dorsey family descendant Beth Kissel and me hosting a “Victorian Christmas” fundraiser at the unrestored, and unheated, Holliday House (I’m the one shivering in the red plaid skirt).

And winters are mighty chilly! This is Dorsey family descendant Beth Kissel and me hosting a “Victorian Christmas” fundraiser at the unrestored, and unheated, Holliday House (I’m the one shivering in the red plaid skirt).

So I learned how hard it is to run a small museum, always looking for money, using every creative opportunity for publicity and funding. My volunteers and I gave house tours and ladies’ group talks and cemetery walks. We put on Old South Balls and held auctions. I wore my blue velvet gown so often that the children at our local elementary school started calling me Mother Goose. A paranormal investigator who came to the house looking for spectral sightings thought I was the ghost of the Holliday House. “The lady in blue!” she cried as I drifted down the staircase to the breezeway between the twin parlors.

“That’s the woman who haunts the Holliday House!” Maybe someday, I thought. But not yet.

“That’s the woman who haunts the Holliday House!” Maybe someday, I thought. But not yet.

By the way, we did have one spectral sighting, sort of: a face in the upstairs window when no one was there, and that looks a lot like one of the members of the Dorsey family that once owned the house…

But that’s another story and this one is about the Hollidays and their relatives. Like a girl named Scarlett O’Hara, who once stayed at the Holliday house when it was being used to board students at the Fayetteville Academy.  Oh, did I say Scarlett? I meant Annie Fitzgerald, of course, an easy mistake to make, as both of them were born in big houses on cotton plantations in nearby Jonesboro, and both of them had Irish-born fathers and mothers with green velvet curtains hanging in their parlor windows, the curtains being the only valuable thing left when the Yankees came through and ravished the countryside. But Annie was real and Scarlett was invented — by Annie’s granddaughter, a writer named Margaret Mitchell.

Oh, did I say Scarlett? I meant Annie Fitzgerald, of course, an easy mistake to make, as both of them were born in big houses on cotton plantations in nearby Jonesboro, and both of them had Irish-born fathers and mothers with green velvet curtains hanging in their parlor windows, the curtains being the only valuable thing left when the Yankees came through and ravished the countryside. But Annie was real and Scarlett was invented — by Annie’s granddaughter, a writer named Margaret Mitchell.

The story about Scarlett attending the Fayetteville Academy is on page two of Gone With the Wind. The stories about Annie come from family history, as Annie was related to the Hollidays, her cousin Mary Ann Fitzgerald being married to the brother of the man who built the Holliday House. Don’t worry if that’s a bit confusing – it’s what we call kin in the South!

Annie Fitzgerald had another cousin as well, a girl named Mattie Holliday who also lived in Jonesboro and visited at the Holliday House. This is a photograph of Mattie:

Annie Fitzgerald had another cousin as well, a girl named Mattie Holliday who also lived in Jonesboro and visited at the Holliday House. This is a photograph of Mattie:

And this is Margaret Mitchell’s description of Melanie Hamilton in Gone With the Wind:

“She was a tiny, frailly built girl, who gave the appearance of a child masquerading in her mother’s enormous hoop skirts – an illusion that was heightened by the shy, almost frightened look in her too large brown eyes. She had a cloud of curly dark hair which was so sternly repressed beneath its net that no vagrant tendrils escaped, and this dark mass, with its long widow’s peak, accentuated the heart shape of her face. Too wide across the cheek bones, too pointed at the chin, it was a sweet, timid face but a plain face, and she had no feminine tricks of allure to make observers forget its plainness. She looked – and was, as simple as earth, as good as bread, as transparent as spring water.”

Those words could have described Mattie Holliday, as well. And there’s one more interesting similarity between Melanie and Mattie: years later, Mattie Holliday became a nun and took the name Sister Melanie. That was how she was known when Margaret Mitchell visited with her as an old woman at Saint Joseph’s Infirmary in Atlanta. Mitchell is said to have asked her if she could name a character after her in the story she was writing, to which Sister Melanie replied, “Just make her a good person.”

And this is Margaret Mitchell, posing at the desk where she wrote Gone With the Wind. Her home at the time is now the Margaret Mitchell House Museum in Atlanta.

But we’ve strayed away from John Henry Holliday – or have we? Because as the story goes, when John Henry was young he and his cousin Mattie Holliday were best of friends, and sweethearts when they were both teenagers. In fact, some folks say that it was their tragic love affair that sent him West and her to the convent. We’ll never know for sure until their rumored love letters reappear, but we do know that they kept up a correspondence until the end of his life. It’s even mentioned in his obituary in Colorado. And what an amazing serendipity it would be: Doc Holliday being in love with Melanie from Gone With the Wind – like literature and legend come together, the Old South meeting the Wild West and falling in love.

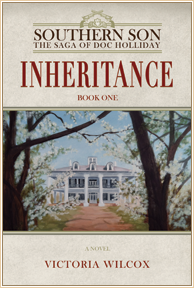

Which is the next part of this story, where I become an author, too, writing an epic historical fiction called The Saga of Doc Holliday.

Original cover for the first edition of the The Saga of Doc Holliday. In 2019, Inheritance will be retitled Southern Son with new cover art.

I didn’t start out to be a novelist. I was just answering TV and newspaper reporters’ questions about the people behind the Holliday House. But every time I was interviewed, the reporters got their facts wrong. So I made up a fact sheet for their reference, and they still got it wrong. Then I wrote out an eight page handout, detailing dates and names – and they still got it wrong, printing things I hadn’t said and drawing fire from Holliday family descendants who thought I was novelizing. Well, why not? Maybe I should leave the confusing facts to the historians and use them as a basis for a well-researched historical fiction instead. Then people who didn’t usually read history could read the history, wrapped around a great story. And it would be so easy: just take what had already been written about Doc Holliday and dramatize it, then add in his youth in Georgia and the Mattie Holliday information and connect it all to Margaret Mitchell. Simple!

Well, that’s what I thought, until I tried to make a timeline of his life out west based on those previously printed histories – and found that the lines didn’t connect properly and the accepted facts about Doc Holliday didn’t add up. He couldn’t be both here and there, couldn’t do this at the same time he did that, couldn’t be running from death and trying to kill himself in the very same beleaguered breath. Oh, I wasn’t the first writer to see the inconsistencies in the supposed facts; others had run into them too and tried to explain them away by saying that Doc Holliday was, well, crazy. But crazy doesn’t account for dates that don’t add up and timelines that don’t connect. Maybe, just maybe, the “facts” weren’t facts at all.

So I started researching on my own, going back to the first source materials like wills and deeds and court documents (what we call Primary Sources) and rereading old newspaper accounts and memoirs and letters and interviewing family members (what we call Secondary Sources). Of course, to get to these sources I often had to travel to the places where they were, which meant following Doc Holliday all over the country, from Georgia to Philadelphia to St. Louis, from Texas to Colorado to New Mexico and Arizona, even down to New Orleans and up the Mississippi River. And somewhere along the way, his story began to make sense. He wasn’t both here and there – he was here, then took a trip no one had mentioned before, then came back and went there because…

It was the “because” that fascinated me, finding out how and why an obscure Southern boy became a Western legend. And that’s how and why I became a nationally known expert on the life of Doc Holliday, advisor to several biographers, and contributor to historical journals and meetings. In trying to dramatize his life, I’d discovered his life. Or a lot of it, anyway, enough to fill three volumes of novelized reality as I relived his life from childhood to his last days.

It took me eighteen years to tell the whole adventurous story of The Saga of Doc Holliday, a bit longer than it took Margaret Mitchell to write her epic saga with nearly the same number of pages. But she didn’t have much else to do at the time, and I’ve run a museum, taught English, written and produced several musicals, managed a dental practice, raised four children and welcomed six perfect grandchildren to the world while writing The Saga of Doc Holliday. Really, it’s a miracle the story got done at all!

Across eighteen years: This is my family dressed for an Old South Ball fundraiser in the early days of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House Museum. Ross was too young for such festivities at the time and stayed home with a babysitter…

Across eighteen years: This is my family dressed for an Old South Ball fundraiser in the early days of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House Museum. Ross was too young for such festivities at the time and stayed home with a babysitter…

…and this is me on one of my research trips, this time to another Holliday House, the home where John Henry spent his teenage years in Valdosta, Georgia. Ross took this picture. He was a senior in high school by then. It’s been a lifetime adventure!

…and this is me on one of my research trips, this time to another Holliday House, the home where John Henry spent his teenage years in Valdosta, Georgia. Ross took this picture. He was a senior in high school by then. It’s been a lifetime adventure!

Oh, about the seemingly random “dental practice” thing – that would be because of the real Doc in my life, my husband, Ronald C. Wilcox, DDS, a Fayette County dentist. I put him through dental school and have learned a thing or two about dentistry, which helped me to have a special understanding of John Henry Holliday, DDS, a Fayette County related dentist. I don’t think any other writer has understood what Doc’s professional education meant to him and how it molded the man he became. It’s been a useful coincidence.

And as long as we’re talking about coincidences, I suppose I should mention November the 8th. That’s the day that Doc Holliday died. It’s also the date that Margaret Mitchell was born, and the date that I was born, as well. Which may be why the house was whispering to me: we had something in common and a story that needed telling. You might say it’s been my legacy.

And now the story begins in Southern Son, the first book in The Saga of Doc Holliday. I think Doc and Mattie and Margaret would have liked it. I hope you will, too!