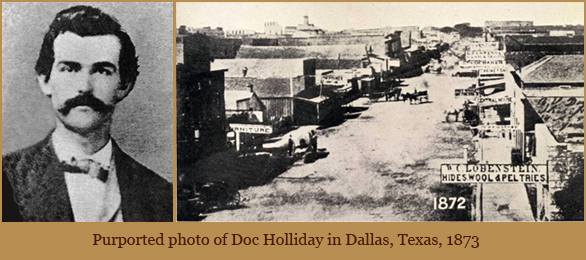

According to popular legend, Doc Holliday left home and went west because he was diagnosed with consumption and told that he had to go to a kinder climate to save his life. And that’s partly true. He was eventually diagnosed with consumption (though when or where, we don’t know) and he did go to the western Territory of New Mexico for his health. But that was years after he left Georgia, after he’d already made a name for himself in several other states. The first place he went after leaving home was Dallas, Texas, which is in the South, not the West, and which did not have a kinder climate. The Dallas weather was much like Georgia, hot and humid in the summer, cold and humid in the winter. It had also been recently closed down by a yellow fever epidemic and was famous for being the second least healthy place in the country to live, right behind the bayous of Louisiana. No one would go there for his health.

So what was it that made John Henry Holliday leave home? The more likely cause of his western exodus wasn’t sickness, but a shooting—a story told in various versions by people who knew him personally, most notably by lawman Bat Masterson. As Masterson tells it, near to the South Georgia village where Holliday was raised ran a little river where a swimming hole had been cleared, and where he one day came across some black boys swimming where he thought they shouldn’t be. He ordered them out of the water and when they refused to go, he took a shotgun to them and “caused a massacre.” In the troubled days of Reconstruction, his family thought it best that he leave the area, so he moved to Dallas, Texas. The village, of course, was Valdosta, and the river was the nearby Withlacoochee.

Bat Masterson’s story first appeared in Human Life Magazine in 1907, then was repeated in newspapers across the country at a time when most of the men who’d known Doc Holliday were still alive and could have refuted the story—but no one ever did. And there were other versions of the story told by people who lived in Valdosta at the time of the shooting, although they disagree on the number of casualties. None of the locals mentioned sickness as a reason for his leaving Georgia, but they were still talking about the shooting on the Withlacoochee decades after his death. The following report is from the Valdosta Times in 1931, based on the recollections of John Henry’s favorite uncle, Tom McKey:

“Accompanied by Mr. T. S. McKey…John one day rode out to a point northwest of the city which was noted throughout this section for its fine ‘washhole.’ Arriving there, they discovered that several negroes had been throwing mud into the water and stirring it up so that it was unfit to swim in. Holliday began scolding the negroes and one of them made threatening remarks back to him. John immediately got his buggy whip and proceeded to punish this hard-boiled negro. The negro fled and returned in a few minutes with a shot gun.

He shot once and sprinkled Holliday with small bird shots. Holliday promptly got his pistol and pursued the fleeing negroes. When the negro who had shot at him saw that the youth meant business, he took to his heels and could not be caught.”

No matter the body count, the story is generally consistent in the events, and although disturbing for its racist overtones, it’s true to the tenor of the times of Reconstruction. And it’s not surprising that, given those times, the family would report a less violent version. What is surprising is that, given the opportunity to deny the story completely and blame Holliday’s exodus from Georgia on a case of consumption, they did not.

So where did that “Doc Holliday left Georgia for his health” story come from? Turns out, that story was never told in Doc’s lifetime—or by anyone who actually knew him—first appearing nearly fifty years after his death in 1931’s Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal. The book’s author, Stuart Lake, had hoped to write a true biography of the famous lawman that would include stories of his friend Doc Holliday, but unfortunately found Wyatt to be the strong, silent type without much to say. Over the course of their eight interviews, Lake remembered the 82 year-old Wyatt Earp as being “illiterate” and his speech “at best monosyllabic.” In other words, Wyatt Earp was a terrible interview and Lake had to elaborate much of the story himself to create a truly heroic epic. So the Doc Holliday we find in Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal is partly fact and partly Stuart Lake’s creative writing. But although the book was essentially a historical novel it was promoted as Wyatt Earp’s first-hand account of the Wild West and became a wildly popular bestseller, spawning movies like Frontier Marshal (four versions) and even the John Ford classic, My Darling Clementine. Then came radio dramas and TV shows like Wyatt Earp and comic books like Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday biographies based mostly on Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, then more movies and more biographies, all spouting the by-now accepted history: Doc Holliday went west to Texas because he was dying of consumption and needed the “high, dry plains of the Western plateau,” as Stuart Lake put it, to heal himself. Even a noted “family portrait” recounted the same tale—likely based on the family’s reading of Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal and remembering that it happened just that way. But just because something has been said over and over again doesn’t make it true—though it can make it legend.

So where did that “Doc Holliday left Georgia for his health” story come from? Turns out, that story was never told in Doc’s lifetime—or by anyone who actually knew him—first appearing nearly fifty years after his death in 1931’s Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal. The book’s author, Stuart Lake, had hoped to write a true biography of the famous lawman that would include stories of his friend Doc Holliday, but unfortunately found Wyatt to be the strong, silent type without much to say. Over the course of their eight interviews, Lake remembered the 82 year-old Wyatt Earp as being “illiterate” and his speech “at best monosyllabic.” In other words, Wyatt Earp was a terrible interview and Lake had to elaborate much of the story himself to create a truly heroic epic. So the Doc Holliday we find in Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal is partly fact and partly Stuart Lake’s creative writing. But although the book was essentially a historical novel it was promoted as Wyatt Earp’s first-hand account of the Wild West and became a wildly popular bestseller, spawning movies like Frontier Marshal (four versions) and even the John Ford classic, My Darling Clementine. Then came radio dramas and TV shows like Wyatt Earp and comic books like Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday biographies based mostly on Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal, then more movies and more biographies, all spouting the by-now accepted history: Doc Holliday went west to Texas because he was dying of consumption and needed the “high, dry plains of the Western plateau,” as Stuart Lake put it, to heal himself. Even a noted “family portrait” recounted the same tale—likely based on the family’s reading of Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal and remembering that it happened just that way. But just because something has been said over and over again doesn’t make it true—though it can make it legend.

Click the book cover below for more info or to order.